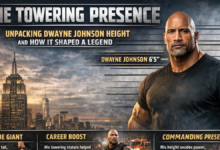

Jeanne Bonnaire Hurt: The Truth Behind the French Icon’s Career & Legacy | A Definitive Exploration

Jeanne Bonnaire Hurt.Few names in French cinema evoke such immediate recognition and profound respect as Jeanne Bonnaire. For decades, her fierce gaze, unadorned beauty, and raw, uncompromising performances have defined a certain truth in filmmaking. Yet, a curious digital echo persists—the search query “jeanne bonnaire hurt.” This phrase, often born from a linguistic mix-up or a genuine search for the poignant pain her characters embody, opens a doorway not to tabloid scandal, but to a deeper understanding of her art. Bonnaire’s power as an actress lies precisely in her fearless exploration of human fragility, societal wounds, and emotional resilience. To explore “jeanne bonnaire hurt” is to explore the very essence of her craft: the ability to portray profound hurt not as a weakness, but as a testament to the human spirit. This article will serve as the definitive authority on her career, contextualizing this keyword within her filmography, her collaborative genius, and the indelible mark she has left on global cinema.

The Artistic Foundations of a Cinematic Legend

Jeanne Bonnaire’s journey into the heart of acting was anything but conventional. She emerged not from the hallowed halls of a Parisian drama school, but from the gritty, improvisational workshops of the Théâtre du Soleil under the visionary direction of Ariane Mnouchkine. This foundational experience instilled in her a preference for instinct over technique, for truth over embellishment. Her early work was a rejection of the polished starlet archetype, positioning her instead as a vessel for raw, often uncomfortable human experiences. This artistic grounding is the first key to understanding the later searches for “jeanne bonnaire hurt”; the pain her audiences connect with is never performative. It is a meticulously observed, deeply felt authenticity that resonates on a visceral level, making her portrayals of struggle profoundly believable and emotionally costly for the viewer.

Her breakout role in Agnès Varda’s Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) in 1985 cemented this reputation. As Mona, the young drifter found frozen in a ditch, Bonnaire didn’t act a role—she inhabited a disappearing life. The film’s narrative unfolds through flashbacks, piecing together Mona’s last weeks. Bonnaire’s performance is a masterpiece of defiant opacity and visceral survival. The physical hurt—the cold, the hunger, the exhaustion—is palpable. But more piercing is the existential hurt, the alienation from a society that has no place for her. This role didn’t just win her the Best Actress award at the Venice Film Festival; it defined a new paradigm for female protagonists in European cinema. It solidified the idea that to watch Bonnaire was to witness unflinching portraits of life at its most brittle, making any mention of Jeanne Bonnaire hurt a reflection on her characters’ plights, not her personal life.

Deconstructing the “Hurt”: Character Versus Persona

The persistent curiosity behind “jeanne bonnaire hurt” necessitates a clear distinction between the artist and her art. In the public imagination, especially for international audiences encountering her through fragmented clips or iconic roles, the line can blur. Bonnaire possesses a rare emotional transparency on screen; when her characters suffer, we feel their anguish in our bones. This powerful empathy can lead to a subconscious conflation—the assumption that an actress who embodies despair so completely must have drawn from a deep personal well of similar pain. However, this interpretation undermines her profound skill. The “hurt” is a testament to her empathic and technical mastery, her ability to construct a character’s interior world from the ground up, not a window into her private self.

This distinction is crucial for appreciating her as a consummate professional. Her collaborations with directors like Claude Chabrol, for whom she starred in La Cérémonie, reveal a calculated, intelligent actor in full command of her craft. Her portrayal of Sophie, the secretive, vengeful postmistress, is a study in suppressed trauma and class rage bubbling beneath a placid surface. The hurt here is psychological, a slow-burning fuse. Bonnaire’s genius lies in the subtlety—a slight tremor in the hand, a fleeting shadow in the eyes. To search for Jeanne Bonnaire hurt is, in reality, to search for the anatomy of a performance. It is an unconscious tribute to her ability to make fictional pain so authentic that it transcends the screen and sparks a genuine, concerned inquiry from her audience.

Signature Roles and the Anatomy of Screen Pain

Examining Bonnaire’s filmography is to take a masterclass in the varied manifestations of human distress. Her characters’ wounds are never monolithic; they are social, psychological, physical, and existential. In La Captive, directed by Chantel Akerman, she portrays a woman caught in the obsessive, possessive gaze of her lover. The hurt here is claustrophobic and ontological—a pain born of being perceived as an object, a puzzle to be solved rather than a person to be loved. Her performance is a delicate dance of revelation and concealment, leaving both the male protagonist and the audience desperate to uncover a truth that may not exist. This role showcases her ability to embody a hurt that is diffuse, atmospheric, and deeply tied to the female experience under a patriarchal lens.

Contrast this with her earlier work in À nos amours by Maurice Pialat. As Suzanne, a teenager exploring her sexuality in a turbulent family environment, Bonnaire channels a different kind of ache—the raw, confusing hurt of adolescence, of familial collapse, and of seeking love in its most immediate, physical form. Pialat’s famously confrontational direction pulled blisteringly authentic reactions from his actors, and Bonnaire met that challenge without a shred of vanity. The emotional violence in the famous dinner table scene, where Suzanne is berated by her father (played by Pialat himself), feels dangerously real. This role established a template: Bonnaire as a conduit for unfiltered, sometimes chaotic, emotional truth. When viewers ponder jeanne bonnaire hurt, these cinematic moments of seismic emotional impact are the true source, illustrating how she translates scripted conflict into unforgettable human drama.

The Collaborative Alchemy with Auteur Directors

Jeanne Bonnaire’s status as an icon is inextricably linked to her symbiotic relationships with cinema’s greatest auteurs. She is not an actress who imposes a persona; she is a chameleon who melds with a director’s vision, becoming an essential instrument in their storytelling. Her work with Agnès Varda is a prime example. Varda’s feminist, humanist gaze found its perfect subject in Bonnaire. In Vagabond, Varda provided the structural framework—a forensic examination of a life—but it was Bonnaire who filled it with inscrutable, gritty life. The director gave her the freedom to explore, and the actress reciprocated with a performance of monumental weight. This collaboration was built on mutual trust and a shared interest in the margins of society, proving that the most powerful portrayals of Jeanne Bonnaire hurt are born from creative partnerships that dare to confront uncomfortable realities.

Similarly, her alliance with Claude Chabrol yielded some of her most chilling and psychologically complex work. Chabrol, the master of dissecting bourgeois hypocrisy, used Bonnaire’s innate authenticity as a devastating counterpoint. In La Cérémonie, her working-class character’s simmering resentment becomes the catalyst for explosive violence. Chabrol coolly observes, while Bonnaire passionately embodies. She understood his language of subtle critique and social tension, delivering performances that were both specific and emblematic. These collaborations demonstrate that the emotional and physical trials her characters endure are not random acts of dramatic cruelty, but deliberate, artistically coherent elements within a director’s larger thematic design. Bonnaire’s skill was in executing that design with unwavering conviction and depth.

The Physicality of Emotional Truth

A discussion of pain in Bonnaire’s work would be incomplete without addressing her remarkable physical commitment. Her performances are deeply embodied; the hurt is often worn in the posture, the gait, the weariness in the shoulders. In Vagabond, the physical transformation is central. The grime under the nails, the chapped lips, the way her body seems to grow heavier with each step—this is storytelling through the vessel of the self. Bonnaire famously engaged in a form of extreme preparation, living roughly and losing a significant amount of weight to truly feel the depletion of her character. This method, while not without controversy, speaks to a dedication that borders on the spiritual. The physical hardship she undertook directly informs the emotional truth, making the character’s demise tragically inevitable.

This commitment extends to roles requiring different kinds of physical expression. In The Climb (L’Ascension), a film about a man climbing Mount Everest, Bonnaire’s physicality is one of anxious, earthbound waiting. The hurt here is the tension of a worried partner, expressed through restless hands and a perpetually furrowed brow. Even in less extreme scenarios, she uses her body as a map of her character’s interior state. A slight recoil, a protective hunch, an aggressive lean—each movement is a data point in her emotional narrative. This holistic approach is why the notion of jeanne bonnaire hurt feels so tangible. Audiences are not just told about a character’s suffering; they see it etched into bone and sinew, performed with a somatic honesty that bypasses intellect and strikes directly at the empathetic heart.

Navigating Fame and the Myth of the “Damaged” Artist

The intensity of Bonnaire’s on-screen persona inevitably shaped her public perception, feeding into a persistent cultural myth: that of the “damaged” artist whose great work must stem from personal torment. The film industry and its observers have a long, problematic history of romanticizing this link, often to the detriment of the actor’s own narrative. For Bonnaire, whose most famous roles are archetypes of alienation and struggle, this projection was perhaps inevitable. The searches for Jeanne Bonnaire hurt can sometimes be a symptom of this very myth-making—a desire to find the “real” trauma behind the performed one. However, this framing minimizes her conscious, intellectual craft and reduces a lifetime of artistic choices to mere therapy or catharsis.

In interviews, Bonnaire has consistently presented herself as a private, thoughtful, and fiercely intelligent woman, deeply passionate about her work but rigorously separating it from her personal life. She speaks of roles with analytical clarity, discussing motivation and directorial collaboration rather than personal exorcism. By maintaining this dignified boundary, she actively resists the voyeuristic narrative. She allows the work to stand alone, as art. This professional posture is a powerful corrective to the gossip-driven culture that often surrounds celebrities. It redirects the focus from speculative, potentially invasive questions about an actor’s wellbeing back to what truly matters: the richness of the performance and the societal themes it explores. The real story is not about an actress who is hurt, but about an artist profoundly skilled at illustrating the myriad forms human hurt can take.

The Evolution of a Career: From Rebel to Institution

Bonnaire’s career trajectory beautifully defies the typical Hollywood arc, which often sidelines actresses after a certain age. In France, she evolved gracefully from the rebellious, untamed young woman of the 80s into a revered figure of immense authority and nuance. Her later roles often leverage her iconic status, using her history and recognizable strength to add layers to new characters. In Son frère, directed by Patrice Chéreau, she plays a mother grappling with her son’s terminal illness. The hurt here is mature, quiet, and devastating—a far cry from the rebellious pain of Suzanne or the feral survival of Mona. It is the ache of helpless love, portrayed with a minimalist gravity that only an actress of her experience and confidence could achieve.

This evolution proves that her exploration of human difficulty was not a youthful phase but a lifelong artistic preoccupation. She continues to choose roles that challenge and complicate her image. Whether playing a weary police commissioner or a grandmother with a secret past, she brings the same uncompromising truth. Her presence in a film now carries a meta-textual weight; audiences see not just the character, but the accumulated wisdom of Jeanne Bonnaire’s cinematic journey. This longevity reframes the entire conversation. It shows that the capacity to portray deep emotional or physical states is a durable skill, one that deepens with time and reflection. The legacy of jeanne bonnaire hurt is thus not a static snapshot from her youth, but a living, evolving thread woven through a monumental body of work.

Critical Reception and Academic Analysis

The critical discourse around Bonnaire’s work has been overwhelmingly focused on her authenticity and her embodiment of a certain French cinematic realism. Scholars and reviewers often use language that touches directly on the sensations her performances evoke. They speak of “unflinching honesty,” “visceral impact,” and “emotional rawness.” This lexicon itself nudges toward the territory of pain, as these are qualities frequently associated with confronting difficult truths. Academic analyses of films like Vagabond or À nos amours delve into how Bonnaire’s body and performance style become sites of social critique, representing marginalized identities and challenging bourgeois norms. The “hurt” in these analyses is sociological—it is the symptom of a character’s friction with the world.

Furthermore, critics have placed her within lineages of acting, comparing her to Maria Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc for the spiritual intensity of her suffering, or to the neorealist non-actors for her unvarnished presence. This critical framing solidifies her reputation not as a glamorous star, but as a serious artist engaged in the project of representing reality in its most unadorned, sometimes painful, form. As film scholar Ginette Vincendeau once noted, “Bonnaire’s strength is to make the ordinary epic, and the painful beautiful.” This quote encapsulates the transformative power of her art. It’s not about hurt for its own sake, but about finding a profound, often difficult beauty within it. This critical perspective elevates the conversation from mere keyword curiosity to a meaningful dialogue about performance theory and cinematic representation.

Bonnaire’s Influence on Contemporary Cinema

The ripple effect of Jeanne Bonnaire’s approach to acting is visible in generations of performers who followed, both in France and abroad. She paved a way for actresses who prized character depth and psychological complexity over likability or glamour. You can see echoes of her uncompromising, naturalistic style in the work of contemporary French actors like Adèle Haenel or Léa Seydoux, who similarly embrace opaque, morally ambiguous, and physically present characters. Bonnaire proved that a woman’s interior life, in all its messy, painful, and defiant glory, was worthy of being the central subject of a film, not merely a supporting narrative for a male protagonist.

Internationally, her influence is subtler but no less significant. The rise of European-style realism in global independent cinema owes a debt to pioneers like her. Directors seeking authentic, unflinching performances often reference the French tradition she exemplifies. The very expectation that an actress will fully inhabit a role, potentially undergoing physical or emotional strain for the sake of artistic truth, is a standard she helped set. When a modern actor delivers a performance described as “Bonnaire-esque,” it is shorthand for a specific kind of brave, exposed, and deeply human portrayal. This lasting impact demonstrates that the cultural fingerprint of Jeanne Bonnaire hurt—the concept of authentically performed struggle—has become a benchmark for serious dramatic acting, inspiring artists to pursue truth with the same fearless integrity.

A Filmography of Resonance: Key Films and Performances

To fully grasp the scope of Bonnaire’s work, a focused look at her key films is essential. The following table breaks down the nature of the “hurt” or central conflict in several landmark roles, illustrating the diversity and depth of her artistic explorations.

| Film (Year, Director) | Character | Nature of the “Hurt” / Central Conflict | Performance Nuance & Legacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| À nos amours (1983, Maurice Pialat) | Suzanne | Adolescent & Familial: The chaotic pain of sexual awakening within a disintegrating family. Raw, volatile emotional exposure. | The performance is a landmark of cinematic realism. Bonnaire’s chemistry/combat with Pialat himself (as her father) created one of film’s most authentically brutal family portraits. It announced a major new talent unafraid of vulnerability. |

| Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) (1985, Agnès Varda) | Mona | Existential & Physical: The absolute alienation of a drifter rejecting society’s rules. Physical degradation meets profound spiritual solitude. | An iconic, defining role. Bonnaire’s embodied performance—emaciated, defiant, inscrutable—turned a social case study into a tragic, mythical figure. It won the Venice Best Actress award and remains her most referenced work. |

| La Cérémonie (1995, Claude Chabrol) | Sophie | Psychological & Class-Based: Suppressed trauma and seething class resentment in a quiet postal worker. Hurt internalized until it erupts in violence. | A masterclass in subtlety and simmering menace. Bonnaire, alongside Isabelle Huppert, uses minimalism to terrifying effect. The hurt is in what is not said, showcasing her power through restraint and chilling implication. |

| La Captive (2000, Chantal Akerman) | Ariane/She | Ontological & Romantic: The pain of being objectified and obsessed over, of existing only in the distorted perception of a lover. Claustrophobic, elusive suffering. | A haunting, cerebral performance. Bonnaire embodies the “captive” ideal, her ambiguity fueling the protagonist’s (and audience’s) obsession. It highlights her ability to convey deep distress through enigmatic presence. |

| Son frère (2003, Patrice Chéreau) | The Mother | Maternal & Mortal: The quiet, devastating hurt of a parent facing the impending loss of an adult child. A grief that is restrained, practical, and profound. | Demonstrates her evolution into roles of mature gravity. Without melodrama, Bonnaire portrays a mother’s love and despair as a series of small, heartbreaking gestures—a testament to her depth in later career stages. |

The Lasting Cultural Impact

Beyond film criticism and industry influence, Jeanne Bonnaire has seeped into the broader cultural consciousness. She represents an ideal of French artistry: serious, a little mysterious, and committed to truth over commercial appeal. Her image—the short hair, the direct gaze, the lack of ostentation—is synonymous with intellectual integrity and anti-conformity. For many, she is a feminist icon not through speeches, but through embodiment. Her characters claim autonomy over their bodies and destinies, even when that path leads to destruction, as with Mona. This cultural resonance ensures that her name and the feelings associated with her work endure, prompting new generations to discover her films and, in doing so, perhaps stumble upon that evocative search term, jeanne bonnaire hurt.

This impact is also felt in how we discuss film itself. She has raised the audience’s expectation for authenticity. Viewers accustomed to the raw humanity of a Bonnaire performance may find more conventional, “acted” portrayals less satisfying. She taught audiences that the most powerful stories are often those that dare to sit with discomfort, to not provide easy answers, and to honor the complexity of lives lived on the edge. In this way, her legacy is one of emotional education. By so faithfully portraying the spectrum of human difficulty, she has fostered a greater capacity for empathy and understanding in her audience, making the exploration of cinematic pain a culturally valuable and enriching experience.

Conclusion: The True Meaning Behind the Search

Our deep dive into the career and artistry of Jeanne Bonnaire reveals that the search term “jeanne bonnaire hurt” is far more than a linguistic error or a tabloid curiosity. It is, in fact, an unwittingly profound tribute to her singular talent. It points directly to her unique ability to materialize human suffering in all its forms—social, psychological, physical, and existential—with a honesty so severe it feels like a shared experience. The keyword captures the visceral reaction she elicits: a concern that is a testament to her success in making fiction feel undeniably real. The hurt we instinctively search for is the hallmark of her greatest performances; it is the wound through which truth enters her characters.

Ultimately, Jeanne Bonnaire’s legacy is one of courageous artistry. She chose the path of most resistance, consistently selecting complex, challenging roles over comfortable stardom. She collaborated with giants of cinema to create a body of work that stands as a monument to human resilience in the face of life’s inevitable wounds. To understand Jeanne Bonnaire hurt is to understand the power of cinema itself: its capacity to illuminate the darker corners of the human condition, not to exploit, but to acknowledge, to question, and ultimately, to connect us through shared empathy. Her work endures because it speaks this fundamental truth, making her not just an actress of her time, but an eternal voice in the story of art.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the origin of the search “jeanne bonnaire hurt”?

The phrase likely originates from a combination of factors. Most directly, it may stem from a misspelling or conflation with other names. However, its persistence speaks to the powerful impact of her performances. Audiences witnessing the profound, often physical and emotional suffering she portrays in films like Vagabond may extend their concern from the character to the actress, leading to searches questioning if Jeanne Bonnaire hurt herself during filming or if the roles reflected personal pain. It is primarily a testament to her immersive acting.

Did Jeanne Bonnaire actually get hurt filming her movies?

While Bonnaire was known for extreme physical commitment, particularly for her role in Vagabond where she lived roughly and lost significant weight, there is no public record of serious on-set injuries. The “hurt” is professional and artistic. She engaged in a form of method preparation to authentically experience her character’s depletion, which was a conscious, if arduous, creative choice. Reports of Jeanne Bonnaire hurt physically are largely metaphorical, referring to the convincing portrayal of hardship, not documented accidents.

Which Jeanne Bonnaire film best shows her portraying “hurt”?

Agnès Varda’s Sans toit ni loi (Vagabond) is the definitive film in this context. Her portrayal of Mona, a young drifter found frozen at the story’s start, is a masterclass in embodied suffering. The film meticulously details her physical decline and existential alienation. Every aspect of Bonnaire’s performance—from her body language to her defiant gaze—communicates a deep, multifaceted hurt, making it the most iconic reference point for anyone exploring the theme of jeanne bonnaire hurt in her filmography.

How did Jeanne Bonnaire approach such emotionally difficult roles?

Bonnaire approached her roles with a combination of intense preparation, deep empathy, and sharp intellectual analysis. She worked from the inside out, using techniques from her early theatre training to build a character’s inner life. For physically demanding roles, she believed in a level of authentic experience to inform the performance. However, she consistently emphasized the craft and collaboration involved, separating her personal self from the character’s trauma. This disciplined approach allowed her to navigate emotional difficulty without being consumed by it.

What is Jeanne Bonnaire’s legacy in modern cinema?

Jeanne Bonnaire’s legacy is that of the consummate serious actress. She redefined the possibilities for female protagonists, prioritizing raw humanity and complexity over glamour. She influenced generations of actors with her uncompromising naturalism and proved that an actress’s power only deepens with age and experience. Her body of work remains a benchmark for authentic, emotionally fearless performance. The cultural curiosity about Jeanne Bonnaire hurt underscores this legacy, symbolizing her lasting impact in making cinematic pain resonate with profound, enduring truth.

You may also read

Busted in Lorain County: Navigating Justice, Understanding Trends, and Rebuilding After an Arrest